Agile Methodologies: Comparing XP and Scrum

- 8 minutes read - 1527 wordsTransitioning from XP to Scrum

Today I will discuss two Agile frameworks: Extreme Programming (XP) and Scrum. After working in an XP environment for several years, I’ve recently started on my first Scrum team. A lot of the content in this post is based on my own experiences with these two frameworks. Please note that these methodologies can vary slightly from place to place.

Wait, what’s Agile again?

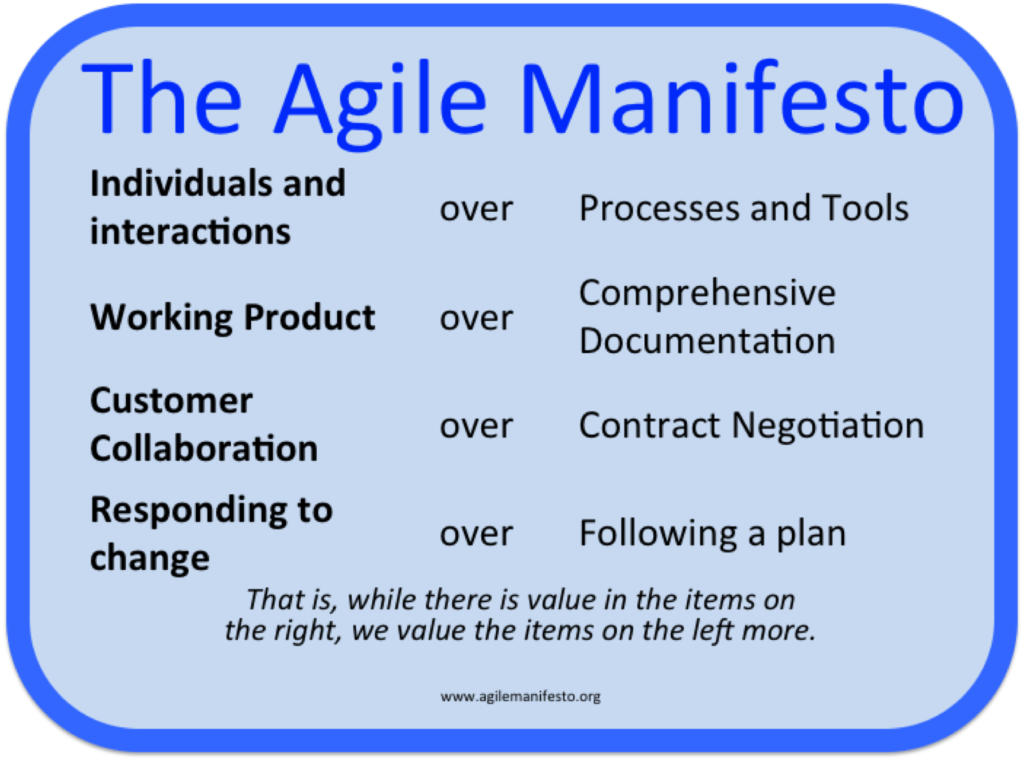

The idea of Agile started with the Agile Manifesto. The creators of this document recognized that building software is unlike factory manufacturing or constructing a building. There are many unknowns in software, and Agile is an attempt to improve the approach of building software.

Okay cool, so now we know where Agile came from, but the manifesto was just the beginning. Much like the Constitution of the United States, people working in the software industry had to interpret the meaning of this concise document. This led to several different flavors of Agile. We will look at two of them today. Let’s breakdown some of the fundamental concepts of XP and Scrum and analyze how they differ.

Two Agile Frameworks

Extreme Programming was founded by Kent Beck in 1996. XP is an Agile framework that focuses on how to deliver software quickly and heavily relies on feedback cycles and input from the end user. XP requires it’s practitioners to engage in several engineering practices like pair programming, test driven development, continuous integration, and incremental design.

Scrum was founded by Jeff Sutherland and Ken Schwaber in 1993. According to Scrum Guides, Scrum is a lightweight framework that helps people, teams, and organizations generate value through adaptive solutions for complex problems. The pillars of Scrum are transparency, inspection, and adaptation. Scrum has five events that implement these pillars: The Sprint, Sprint Planning, Daily Standup, Sprint Review, and Sprint Retrospective.

XP and Scrum Differences

XP and Scrum differ in their values, execution, and engineering practices. However, at the end of the day their common goal is to produce high quality software that their customers will use and enjoy. How they go about achieving this goal is where the differences reside.

Sprint Cycles

What’s a sprint?

A sprint is a repeatable fixed event of one month or less to create consistency for a team. A new sprint starts immediately after the conclusion of the previous sprint.

In XP, sprints are often referred to as iterations. In my experience, they are not taken as seriously as in the Scrum world. When I worked in an XP environment our iteration cycle was weekly. Every Monday, we moved new user stories into our active backlog. Our backlog was always flexible to change depending on the needs of our consumers. Once the backlog was prioritized, stories were pulled from the top. No cherry-picking!

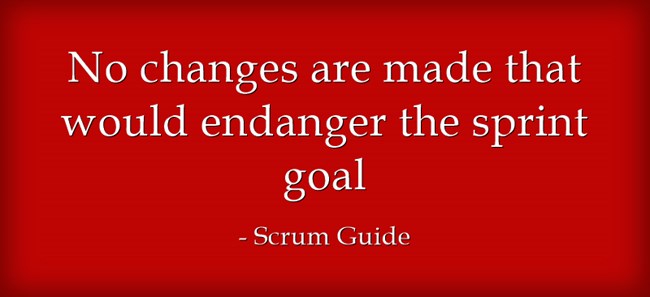

In Scrum, sprints are referred to as the heart beat of Scrum. They are where ideas are turned into value. My current Scrum team has sprints that last for two weeks. Scrum is very strict about not changing commitments during a sprint.

The stories for the sprint are usually divided amongst the developers. On my team, the devs choose the stories they would like to work on for the upcoming sprint. The order in which the stories are worked on is not important in most cases—as long as everything is complete by the end of the sprint.

The practice of choosing what to work on up to a week or so in advance is very new and strange to me. I’ve been trying not to pick the easiest thing available and instead trying to pick a challenging story. This forces me to grow. With the support of my product team, I should be capable of completing any task and by doing so gain context on the services in which we support.

Another aspect of the Scrum sprint that is a little awkward to me is imposing deadlines on the team in terms of a sprint goal. When I worked in XP, we weren’t scrambling on a Friday to finish our stories in flight just because it was the end of our iteration. There was no pressure by our product manager to deliver what we had chosen for the backlog that week. Don’t get me wrong—deadlines exist, but we chose the days that we would deploy code to production.

Not getting a story into production was usually not an issue for our teams. Instead, the following Monday we would just add stories, chores, and bugs to our existing backlog as we always do and carry on with any work in progress. Deadline pressures can create a sense of urgency that invite developers to cut corners and bypass quality measures in order to MEET THE DEADLINE. There’s already enough deadlines in the software world, so why do we need to create more for ourselves? I understand that teams may need to give themselves some kind of time box to stay in a flow, but time estimates are very difficult in software—I don’t think a team should be scrutinized if they do not finish some of their stories by the end of the sprint.

Engineering Practices

Scrum has no required engineering practices that are imposed on product teams. For that reason, this section will be largely dedicated to XP and its practices. Those practices are pair programming, test driven development, continuous integration and incremental design.

Pair Programming

Pair programming is when two developers work on a piece of software together. In my previous lab, we had an open concept office space where each pair had a monitor and keyboard in front of them. The displays were mirrored so whatever I saw on my display, my pair would also see.

There are two roles in pair programming—the driver and the navigator. The role of the driver is to have control of the keyboard and write the code necessary to complete the task at hand. The role of the navigator is to guide the driver, help them when they are stuck, and pay attention to the larger design of the system in order to plan ahead for any choices that need to be made. The roles can be switched amongst the two developers as they wish—anywhere from 30 to 60 mins is a good time frame to stay in one particular role.

Programming with someone else gives both developers accountability, focus, and it’s pretty fun as well! Pairing has its ups and its downs. While being incredibly rewarding, it can also be emotionally draining as you need to be able to communicate your thoughts to someone else while you are both trying to solve a complex problem. When done correctly pair programming results in fewer defects, better design, and a more collaborative team.

Test Driven Development

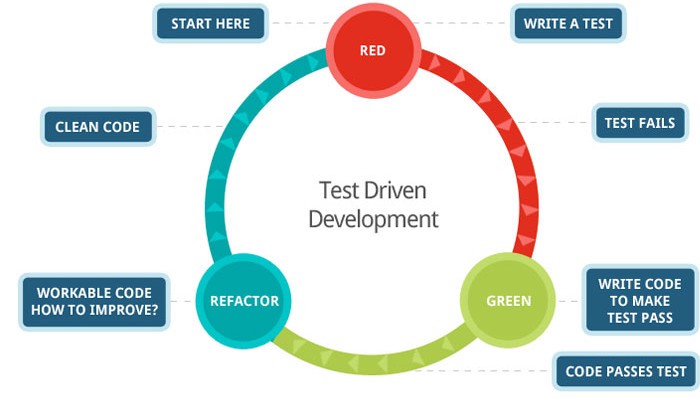

Test driven development (TDD) or test first development is the practice of writing an automated test before writing the production code necessary to make the test pass. The TDD cycle is red, green, refactor.

The sequence is as follows:

- Write a unit test that asserts some new functionality

- Run the test and see it fail

- Write the simplest code required to make the test pass

- Refactor the code in the test and implementation in order to make it more coherent and maintainable

- Repeat

TDD enforces that our code is easily testable. Since we’ve already written the test then it’s very easy to write testable code. Make it fail, make it work, make it better. This feedback loop enables us to solve complex problems by breaking it down into its simplest form and tackling one chunk at a time.

Continuous Integration

“Continuous integration (CI) is a development practice that requires developers to integrate code into a shared repository several times a day.” By working on smaller tasks and doing TDD along the way, developers are able to always have working software that is ready to deploy whenever. This practice naturally leads to more frequent deployments. Frequent deployments can reduce the complexity of change introduced into a system and allow feedback to quickly come from the users of the software. To achieve CI it is common for XP teams to utilize trunk based development, whereby they push all code directly onto the master branch.

Incremental Design

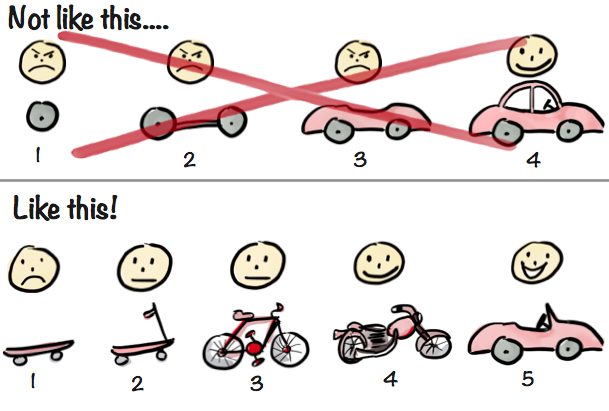

Incremental design was first explained to me by a coworker by using a famous analogy by Henrik Kniberg.

When we are setting out to build a car, we don’t just build a car first. First we build a skateboard and get feedback from our customer. Then we might add a handlebar and make it into a scooter. After more rounds of feedback we get a motorcycle and eventually a convertible.

Incremental design is often coupled with the idea of the Minimum Viable Product (MVP). Building an MVP is all about breaking down a large solution into its smallest useful piece. Focus on the core functionality and reduce unnecessary scope, in order to get the product into people’s hands. This is what incremental design is all about and it’s a core concept of Agile, not only XP.

Continue Reading—Agile Methodologies: Comparing XP and Scrum Part 2

Agile Methodologies: Comparing XP and Scrum Part 2